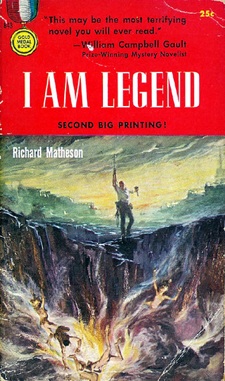

When it comes to horror and science fiction, few literary works have had as great an impact as Richard Matheson’s third novel, I Am Legend, published as a Gold Medal paperback original in 1954. It has been officially adapted into three films, or four if you count Soy Leyenda (1967), a Spanish short that is so obscure it has eluded many a Matheson scholar (including this one), and marked the first use of Matheson’s title, albeit en Español. It has also been ripped off countless times, most recently—and perhaps most egregiously—in the 2007 direct-to-video travesty I Am Omega, produced solely to cash in on that year’s then-forthcoming Will Smith theatrical version.

Because I Am Legend begat George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), it was at least indirectly responsible for the entire zombie subgenre as we know it today. It has been compared to such apocalyptic fiction as Justin Cronin’s The Passage, and clearly made its mark on Stephen King, who has noted that “my first bestseller” was an unauthorized novelization of Matheson’s Pit and the Pendulum (1961) printed in his basement. It doesn’t stop with I Am Legend, because Anne Rice and Chris Carter have cited Matheson’s “Dress of White Silk” and his original Night Stalker as influences upon the Vampire Chronicles and The X-Files, respectively…but I digress.

I Am Legend’s road from page to screen has been a bumpy one, despite an auspicious beginning when England’s Hammer Films, flush with the success of The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Horror of Dracula (1958), hired Matheson to adapt it in 1958. Their planned version, The Night Creatures, was to have been directed by Val Guest, but hit a brick wall when the censors on both sides of the Atlantic decreed that Matheson’s script (included in his collection Visions Deferred), if filmed as written, would be banned. Hammer sold the project to its sometime U.S. distributor, Robert L. Lippert, who had Matheson rewrite it and told him it would be directed by Fritz Lang.

In the event, that version was rewritten once again by William F. Leicester, prompting Matheson to put his Logan Swanson pseudonym on the script, and filmed in Italy as L’Ultimo Uomo della Terra, with Vincent Price being directed by his agent’s brother, Sidney Salkow. Unsurprisingly, given Matheson’s involvement, The Last Man on Earth—as we know it Stateside—is by far the most faithful version. Yet it is hampered by impoverished production values, location shooting in Rome (rarely mistaken for its L.A. setting), and the arguable miscasting of Price, despite his fine work in so many other films Matheson wrote for AIP, which released Last Man in the U.S.

Ironically, The Last Man on Earth is in some ways more faithful to the novel than is The Night Creatures, but since the version Matheson wrote for Lippert has not been published, we cannot assess which elements of Last Man originated with him, and which with Leicester. The Night Creatures introduced a flashback to a birthday party for Robert Neville’s daughter, which was carried over into the film, but relocated the story to northern Canada and gave him an electrified fence and a pistol. Like all subsequent versions, Last Man made the main character (renamed Morgan) a scientist, and introduced the notion of his ability to cure the infected with his blood.

The screenplay for Night of the Living Dead originated with an unpublished and hitherto untitled short story (sometimes referred to as “Anubis”) that was written by Romero and inspired by I Am Legend. Certainly the idea of people barricaded inside a house by a horde of ambulatory corpses who hope to feed on them is similar, and the moody, monochromatic photography of Franco Delli Colli in Last Man echoes that in the even lower-budgeted Night. I don’t know if Romero has also acknowledged Last Man as an influence, but in retrospect, it’s difficult to look at the slow-moving, almost robotic vampires in Salkow’s picture without thinking of the shambling zombies from Night.

Last Man was officially remade three years later by Warner Brothers as The Omega Man (1971), an action vehicle for a machine-gun-toting Charlton Heston, no stranger to apocalyptic SF after Planet of the Apes (1968). At his behest and that of producer Walter Seltzer, married scenarists John William and Joyce Hooper Corrington (who, she admitted, may never have read the novel) transformed Matheson’s vampires into a “family” of light-hating albino mutants led by a former newscaster, Brother Matthias (Anthony Zerbe). Complete with a trendy interracial love interest (Rosalind Cash) and a jazzy score from Ron Grainer, it was fun but a far cry from I Am Legend.

Significantly, the Will Smith version credits both the novel and the Corringtons’ screenplay as its source material, for it is as much a remake of The Omega Man as an adaptation of I Am Legend. Once again, Neville is a military scientist with a high-tech arsenal and home base that would put Morgan’s (or the literary Neville’s) wooden stakes and boarded-up windows to shame. His foes are now light-averse critters called “Dark Seekers,” created with computer graphics and utterly lacking in personality, whereas both I Am Legend and The Last Man on Earth poignantly made the protagonist’s former best friend and colleague, Ben Cortman, the head of the vampire horde.

This is but one way in which screenwriters Mark Protosevich and Akiva Goldsman rob the story of some of its dramatic impact, e.g., Neville’s wife and daughter are killed in a helicopter crash rather than slowly succumbing to the plague. He was previously forced to stake the wife when she returned as a vampire, and the pathetic mutt that he tried fruitlessly to save has been amped up into a heroic canine companion and ally for Smith. Interestingly, Matheson had anticipated this in his Night Creatures script as Neville dubs the dog Friday (in a nod to Robinson Crusoe), allows him to ride shotgun in his station wagon and watches in agony as he is killed by Cortman.

Most altered in the various versions is Matheson’s devastating ending, in which Neville is put to death by those who are infected but control the virus by chemical means, and regard him as the “monster” because some of those he staked were not yet dead. Justifying the novel’s title, it was largely preserved in The Last Man on Earth but softened in The Night Creatures, apparently at Hammer’s insistence, as Matheson recalled in Bloodlines: “I was more willing to make changes” at that early stage in his screenwriting career. There, Neville is led away to the headquarters of the “new society” but told, “you’re too valuable to kill [because of your] immunity to the germ.”

Smith’s Neville is not even unique in his immunity to the plague, and it is not his blood but that of a Dark Seeker successfully injected with his experimental vaccine that he sacrifices himself to save in the theatrical version of the film. In an alternate ending included on the DVD, he returns his captured test subject to their “Alpha Male,” and is allowed to depart with his companions for a colony of uninfected survivors in Vermont. Fortunately, while the planned prequel is expected to use none of Matheson’s material, the novel remains unaltered and available, and in its tie-in editions has generated his biggest sales ever, peaking at #2 on the New York Times bestseller list.

Matthew R. Bradley is the author of Richard Matheson on Screen, due out any minute from McFarland, and the co-editor—with Stanley Wiater and Paul Stuve—of The Richard Matheson Companion (Gauntlet, 2008), revised and updated as The Twilight and Other Zones: The Dark Worlds of Richard Matheson (Citadel, 2009). Check out his blog, Bradley on Film.